Welcome to Health Notes!

Understanding Research - Cause or Consequence. NuttZo Nut & Seed Bars. Healthy Snacking in the US 2024 Report.

Welcome to Health Notes! My free newsletter filled with insights and practical resources for you to reach and maintain health. Be sure to hit the 'Subscribe' button to receive Health Notes right in your inbox. Learn more about the kind of content I publish here.

Coming soon - all subscribers will receive free access to all my archived newsletters, actionable deep-dive articles, commenting in threads, as well as invitations to join me live for Q&A sessions and other special events.

Thank you for reading, sharing, and joining this amazing community!

Welcome to my very first full-length newsletter! After many months of thinking, conceiving, re-conceiving, and receiving feedback from colleagues, it is finally here! Let’s get started!

// Understanding Research / Mistake #1 - Cause or Consequence /

In this series of insights, I reveal common mistakes people make when reading research studies. This includes mistakes made by the study authors, health experts, or the lay person. My intent is not to bash these people. Rather, it is to help you become a smarter and more informed health champion.

We’ll start with a pretty simple one and then advance from there. This first mistake is pervasive across every sector of research, especially in health research, including nutrition studies.

It’s one thing to make this mistake in an obscure field of research (say, when studying the influence of rainfall patterns on frog mating behavior). It won’t really mess with your health.

On the other hand, making this mistake in a nutrition study may drive millions of people to change what they eat, what they avoid, and how they perceive foods, supplements, or other lifestyle behaviors. And that may really mess with your health.

I will focus on research mistakes that can impact your health.

For reasons explained below, conducting human health studies is hard. Most of the published research, and what you may come across online, originates from studies that look at the association between one parameter and one health outcome.

For example, a recent headline states “New research by American Heart Association finds a 91% higher risk of heart disease mortality with intermittent fasting.”

USA Today reports “Results of a study presented at the association's conference in Chicago this week revealed that adults following an eight-hour time-restricted eating schedule have a 91% higher chance of death by cardiovascular disease than those eating within the usual timeframe of 12-16 hours per day.”

Scary, right? And maybe that’s the point. It catches your attention. You click to read further.

But we know better. First of all, this finding was presented as an abstract in a conference. They findings are not reported in a full scientific publication, nor have they undergone peer-review, let alone been published in a reputable journal. The raw data set is not available for independent review.

What is known is the fact that this is an association study. It’s a survey, a retrospective review, a questionnaire-type study, asking subjects to recall what and when they eat. The results are fed into a statistical analysis package to see what connections can be made between participants foods and lifestyle and various health outcomes.

In fact, the researchers explored the association between numerous parameters and numerous health outcomes, simply to see what patterns ‘emerge’.

Indeed, there are numerous challenges in what we might consider a ‘gold standard’ study - ‘the randomized control trial’. Suffice it to say that nutrition studies are hard to do right.

Nutrition is not like rocket science. It’s harder.

In fact, nutrition intervention studies are nearly impossible to do right.

Can they be done in a double-blind fashion? Certainly not! What about time-to-impact of these interventions? For practical reasons, intervention studies are rarely longer than 2 or 4 weeks in length. What if the intervention requires more time to generate its benefit? The reality is that we are completely blinded to the effectiveness of long-term interventions.

So, what do researchers do when it is impossible to generate ‘gold standard’ evidence? They resort to doing the next best thing. To save time. To save money.

They conduct observational studies. These involve collecting the dietary habits of people and then looking at their health status at some future point in time. Data is collected through surveys, questionnaires, or extracted by data scientists from large sets of anonymized medical records. The researchers may never come in contact with a single study participant.

From there, it’s simply a statistical matching exercise. The data is summed, tabulated, and paired to various health outcomes, sometimes in a hypothesis-driven manner, but often without a coherent hypothesis to see what pops out as a notable finding. These studies are known as a ‘fishing experiments’, for obvious reasons.

Hand here is the rub. When you roll the dice enough times, you will surely get an interesting combination of results. And that’s the problem with these studies.

Step 1 - Collect or access a large number of ‘lifestyle’ parameters (how much milk is consumed, how many snacks are eaten in a day, how many hours of sleep, exercise, and so on).

Step 2 - Collect all the accessible health parameters from the same subjects (for example, presence of any chronic disease, BMI, blood pressure, any reliable risk factors, etc.).

Step 3 - Look for connections between these two datasets. That’s all. You are done!

Congratulations. You have a paper to publish!

This approach is seen across the full range of health publications. Even in prestigious science journals. Especially in prestigious science journals.

The lead authors are often data scientists. These authors spend little or no time in the lab. They have little or no face-to-face time with patients. They apply a big data model to health research. The approach can reveal high-level patterns that may be interesting and worth further investigation. But they reveal nothing that should set public health policy. Or drive specific health recommendations at the individual patient level.

Why is this a fraught approach?

There are plenty of reasons. For starters, ask if these studies enroll or include data from a representative population? Do you as an individual reflect the type of individuals included in these studies? How do the results and conclusions apply to you? To your genetic makeup, your upbringing, your habits, your eating style, or a myriad of other lifestyle parameters that are unique to you?

The reality is that they do not. You are very unique in your biology and lifestyle. You should be very cautious in applying findings from these type of studies to your own health.

This is in contrast to intervention studies where a single variable (a specific dietary intervention, for example) is studied under controlled settings. This approach generates a much stronger type of evidence. It reveals more than a statistical association. It can even reveal causal relationships. In other words, a specific intervention causes a specific response!

This is the crux of the issue. We have to separate the studies, the reports, the headlines that are simply associations between two parameters (a certain behavior and a certain outcome) from the studies that report possible causal relationships between a certain behavior and outcome.

Always ask if the observed response is a cause or consequence of the behavior pattern.

Below is a nice summary of these relationships along with real-world examples here:

Thing A caused Thing B (causality)

Thing B caused Thing A (reversed causality)

Thing A causes Thing B which then makes Thing A worse (bidirectional causality)

Thing A causes Thing X causes Thing Y which ends up causing Thing B (indirect causality)

Some other Thing C is causing both A and B (common cause)

It’s due to chance (spurious or coincidental)

Common cause

Common case occurs where some other thing causes both A and B. For example, a study may report that people who drink >4 cups of coffee/day have a decreased chance of developing skin cancer.

Does this mean coffee protects against skin cancer? Not at all! There can be many other explanations that have nothing to do with the biology of coffee or cancer.

One can posit that heavy coffee drinkers work indoors. They work for long hours. This reduces their exposure to direct sunlight (a known risk factor). In this scenario, ‘how many hours spent in the sun’ is a confounding variable. This parameter is common to both observations (coffee drinking & skin cancer). As such, a direct causal link cannot be made.

Keep in mind, when one studies lots of variables operating within a complex system, it is easy to fall into a trap of connecting two independent parameters through a shared, common cause.

These, in my mind, are the most misleading, most misinterpreted, and most dangerous type of studies that we come across in both scientific and lay publications.

Spurious correlations

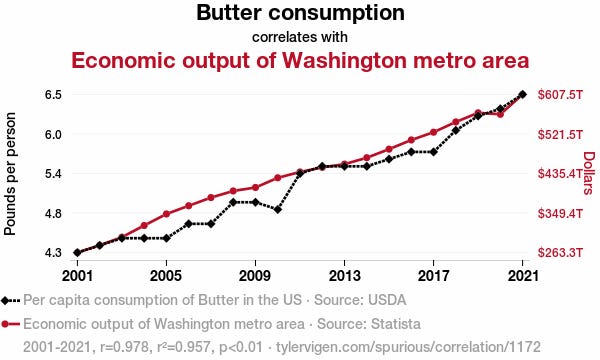

Did you know that butter consumption correlates with the economic output of the Washington DC metro area? This is an evidence-based conclusion, as you can see below.

But it is simply a spurious or coincidental relationship. For fun, here is an AI generated paper that explains and justifies as real this spurious finding.

See more spurious correlations here.

What next

Try this: Enter the following term in the search field of PubMed. Add whatever term you want in place of the underline. See what comes up. And then see if you can identify the erroneous and overstretched conclusions from these studies.

Search PubMed for: “the association between ____…”

Are you inclined to put into action the findings from these studies to better your health. It’s an attractive and natural reaction.

Even I find myself leaning too much into these studies. To better my health. To help troubleshoot the clients that work with me.

If they are safe, what is the harm? This is a difficult issue to untangle. There are no quick answers. I will explore these in upcoming newsletters.

Finally, what about that fasting study I mentioned at the top? The American Heart Association presentation that found a 91% higher risk of heart disease mortality with intermittent fasting. You should, by now, know how flawed a study it is. You may shake your head if you visit the stream of misleading headlines it generated.

Here is a critique of that study if you want to explore further.

That’s it for this episode. In upcoming newsletters of my Understanding Research series, I will cover:

/ Mistake #2 - Sampling / (blood v tissue compartment)

/ Mistake #3 - Kinetics and Flux /

/ Mistake #4 - Endogenous v Exogenous /

/ Mistake #5 - Biomarkers v True Outcomes /

and more…

NuttZo Nut and Seed Butters

Jars & Bars

Organic & Non-GMO options

Free of emulsifiers

High in fat and protein

Low in carbohydrate

Use them as a satiating snack or create your own treats from their recipe pages.

Ingredients (Natural Paleo Power Fuel Smooth): Cashews*, Almonds*, Brazil Nuts*, Flax Seeds*, Chia Seeds*, Hazelnuts*, Pumpkin Seeds*, Celtic sea salt

Ingredients (Chocolate Keto Crunchy): Almonds*, Shredded Coconut, Chocolate Liquor† (Cocoa Beans†), Brazil Nuts*, Pecans*, Monk Fruit (Erythritol, Monk Fruit Extract), Macadamia Nuts*, Flax Seeds, Chia Seeds, Celtic Sea Salt

*dry roasted

†organic

** Note: I have no affiliation or relationship of any kind with this company.

Healthy Snacking in the US

The YouGov 2024 report on US healthy snackers is out. It reveals that a significant portion of American consumers (32%) prioritize health in their snacking choices, with a majority willing to pay extra for organic options.

Highlighting the influence of advertising on purchasing decisions, the report also uncovers that a large segment of these health-conscious snackers, predominantly aged 18-44 and often parents, are considering reducing their meat and dairy consumption.

Despite busy lifestyles limiting time for meal preparation, these consumers are not only spending a notable amount on snacks monthly but are also influenced by brands that align with their values and support social causes. Brands like Yoplait, Blue Almond Diamonds, Special K, Dannon, and Annie’s are leading in popularity among this demographic, which also shows distinct media consumption habits and a growing trust in certain brands.

This trend underscores the evolving preferences of American snackers towards healthier, convenient, and ethically aligned food choices.

YouGov is an international online research data and analytics technology group.

US Healthy Snackers Report 2024 (yougov.com)

My breakfast today

Home-made yogurt (24-hour fermented full fat dairy milk and heavy cream 50/50, strained), organic bulk turmeric, raw honey. Alternatively, I will top with this organic walnuts, strawberries, or raspberries when in season.

Altman, N., Krzywinski, M. Association, correlation and causation. Nat Methods 12, 899–900 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3587